Next: 1.4 Organic Light-Emitting Diodes

Up: 1. Introduction

Previous: 1.2 Organic Semiconductor Physics

Subsections

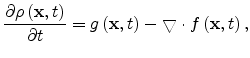

The incoherent dynamics of carriers as well as excitons can be described by a

master equation,

|

(1.2) |

with  denoting the occupation probability of state

denoting the occupation probability of state  and

and

the electron or hole transition rate of the hopping process between the occupied

state

the electron or hole transition rate of the hopping process between the occupied

state  to empty state

to empty state  . Defining

. Defining  as the

chemical potential at the position of state

as the

chemical potential at the position of state  and

and  as the energy of state

as the energy of state

, the occupation probability is

given by the Fermi-Dirac distribution function

, the occupation probability is

given by the Fermi-Dirac distribution function

|

(1.3) |

Assuming no correlations between the occupation probability of different

localized states, the steady-state current between these two sites is

given by

![$\displaystyle I_{ij}=q\left[f_i\left(t\right)\left(1-f_j\left(t\right)\right)\omega_{ij}-f_j\left(t\right)\left(1-f_i\left(t\right)\right)\omega_{ji}\right].$](img104.png) |

(1.4) |

Substituting the Miller-Abrahams rate (1.1) in (1.4) the current becomes

![$\displaystyle I_{ij}=\frac{q\nu_0\exp\left(-2\alpha R_{ij}-\frac{\mid E_i-E_j\m...

...\left[\frac{E_i-\mu_i}{2k_BT}\right]\cosh\left[\frac{E_j-\mu_j}{2k_BT}\right]}.$](img105.png) |

(1.5) |

In the case of low electric field, resulting in a small voltage drop over a

single hopping distance (

), the following

conductance is obtained

), the following

conductance is obtained

![$\displaystyle \sigma_{ij}=\frac{I_{ij}}{\Delta\mu}\propto\exp\left[-2\alpha\mid...

...j}\mid-\frac{\mid E_i-\mu\mid+\mid E_j-\mu\mid+\mid E_i-E_j\mid}{2k_BT}\right].$](img107.png) |

(1.6) |

Here

. This expression was introduced in 1960 by

Miller and Abrahams [7] and is often referred as the Miller-Abrahams

conductance. Equation (1.6) has an important implication. Even if the energies are

moderately distributed, the exponential dependence of

. This expression was introduced in 1960 by

Miller and Abrahams [7] and is often referred as the Miller-Abrahams

conductance. Equation (1.6) has an important implication. Even if the energies are

moderately distributed, the exponential dependence of

on these

energies makes them enormously broadly distributed. This can be used to reduce

the computations of the effective properties of the network, since the

broadness of the distribution of

on these

energies makes them enormously broadly distributed. This can be used to reduce

the computations of the effective properties of the network, since the

broadness of the distribution of

implies that there are many

small conductances that can be removed from the network. This resulting network

is called the reduced network [13].

implies that there are many

small conductances that can be removed from the network. This resulting network

is called the reduced network [13].

Miller and Abrahams [7] were the first to calculate the hopping conductivity  of

semiconductors using reduced networks. They assumed that the statistical

distribution of the resistances depends only on

of

semiconductors using reduced networks. They assumed that the statistical

distribution of the resistances depends only on  and not on the site

energies. This was justified because the experimental data for some

semiconductors indicated that the impurity conduction exhibits a well-defined

activation energy. But Mott [16] pointed out that the exponential dependence of the

resistances on the site energies can not be ignored in most cases. When a carrier

close to the Fermi energy hops away over a distance

and not on the site

energies. This was justified because the experimental data for some

semiconductors indicated that the impurity conduction exhibits a well-defined

activation energy. But Mott [16] pointed out that the exponential dependence of the

resistances on the site energies can not be ignored in most cases. When a carrier

close to the Fermi energy hops away over a distance  with an energy

with an energy  , it has

, it has

sites to choose from, where

sites to choose from, where  is the site density function. In general,

the carrier will jump to a site for which

is the site density function. In general,

the carrier will jump to a site for which  is as small as

possible. The constraint to find a site within a range

is as small as

possible. The constraint to find a site within a range

is given by

is given by

. Substituting

this relation into (1.6) yields

. Substituting

this relation into (1.6) yields

![$\displaystyle G\propto \exp\left[-2\alpha R-\frac{1}{k_BT\left(4/3\right)\pi R^3\rho}\right].$](img114.png) |

(1.7) |

The optimum conductance is obtained by maximizing  with respect to the hopping

distance

with respect to the hopping

distance  as

as

![$\displaystyle G\propto\exp\left[-\left(\frac{T_1}{T}\right)^{1/4}\right],$](img115.png) |

(1.8) |

with

.

Much theoretical work has been done by investigating the mobilities of organic

semiconductors within the framework of GDM [9]. Non-crystalline

organic solids, such as molecularly doped crystals, molecular glasses, and

conjugated polymers, are characterized by small mean free paths for the

carriers, as a result of the high degree of disorder present in the organic

system. Therefore, the elementary transport step is the charge transfer between

adjacent elements, which can either be molecules participating in

transport or segments of a polymer separated by topological defects. These

charge transporting elements are identified as sites whose energy are subjected

to a Gaussian distribution

.

Much theoretical work has been done by investigating the mobilities of organic

semiconductors within the framework of GDM [9]. Non-crystalline

organic solids, such as molecularly doped crystals, molecular glasses, and

conjugated polymers, are characterized by small mean free paths for the

carriers, as a result of the high degree of disorder present in the organic

system. Therefore, the elementary transport step is the charge transfer between

adjacent elements, which can either be molecules participating in

transport or segments of a polymer separated by topological defects. These

charge transporting elements are identified as sites whose energy are subjected

to a Gaussian distribution

where  is the energy measured relative to the center of the density of

states and

is the energy measured relative to the center of the density of

states and  is the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution. Within this distribution, all the states are localized. The

choice of such distribution was based on the Gaussian profile of the excitonic

absorption band, as well as on the recognition that the polarization energy is

determined by a large number of internal coordinates, which vary randomly by a

small amount, so the central limit theorem of statistics holds.

is the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution. Within this distribution, all the states are localized. The

choice of such distribution was based on the Gaussian profile of the excitonic

absorption band, as well as on the recognition that the polarization energy is

determined by a large number of internal coordinates, which vary randomly by a

small amount, so the central limit theorem of statistics holds.

The Gaussian disorder model has been treated by the Monte Carlo simulation

technique based on the Miller Abraham equation [9]. In this simulation

charge transport is described as an incoherent random walk. The carriers start

their motion from randomly chosen sites at one of the boundaries of the system

sample. Their trajectories are specified from the constraint that the

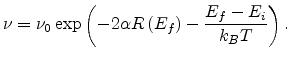

probability for a carrier to jump between two transport sites is

With this technique, TOF measurements can be simulated [9], in which

mobility is derived from the mean arrival time of the carrier at the end of the

sample and from their mean displacement. The predictions made concern the

temperature and electric field dependence of the mobility.

In the Gaussian disorder model, the strength of electronic coupling among sites

is split into separate contributions from the relevant sites, each obtained

from a Gaussian probability density. However, the choice for the off-diagonal

disorder of a Gaussian distribution is not theoretically sustained unlike in

the case of energy disorder, and a more realistic way of representing geometric

disorder has been pursued. One of such attempt is described in [14], in

which an alternative approach comprising positional and orientation disorder is

introduced via fluctuations in the bonds adjoining the various transport sites

rather than site fluctuations. This model gets rid of the unnecessary

corrections between hops and results in overestimating the contribution of the

log hops.

In particular, Gartstein and Conwell's [14] Monte Carlo simulations of hopping

with the elementary jump rate described by 1.1, but in which

where

is a uniformly distributed random variable. In this way,

the different bonds of a given site with its

neighbors are uncorrelated.

is a uniformly distributed random variable. In this way,

the different bonds of a given site with its

neighbors are uncorrelated.

Another approach for the description of positional disorder was presented by

Hartenstein [15], and was also based on Monte Carlo simulations of transport

in a dilute lattice. This treatment employs the GDM, but without the need for

defining a distribution function for the electronic coupling between different

sites. In this case the hopping sites having the nearest neighbors were

grouped in clusters whose size depends on the random intercluster distances,

but ignores any contribution from the random orientation of the transporting

elements. Nevertheless, the model is adequate for low dopant concentrations for

which there are large fluctuations in the intersite distances.

Ambegaokar and coworkers argued that an accurate estimate of  is the critical

percolation conductance

is the critical

percolation conductance  [17], which is the largest value of the conductance

such that the subnet of the network with

[17], which is the largest value of the conductance

such that the subnet of the network with

still contains a

conducting sample-spanning cluster. They divided the network into three

parts.

First, a set of isolated clusters of high conductivity where each cluster

consists of a group of sites connected together by conductances

still contains a

conducting sample-spanning cluster. They divided the network into three

parts.

First, a set of isolated clusters of high conductivity where each cluster

consists of a group of sites connected together by conductances

;

Second, a small number of resistors with

;

Second, a small number of resistors with  of order

of order  , which

connect together a subset of high conductance clusters to form the

sample-spanning cluster, called the critical subnetwork, essentially

the same as the static limit of the reduced network discussed above;

and third, the remaining resistors with

, which

connect together a subset of high conductance clusters to form the

sample-spanning cluster, called the critical subnetwork, essentially

the same as the static limit of the reduced network discussed above;

and third, the remaining resistors with

. The resistors in the

second part

dominate the overall conductance of the network. The critical conductance

. The resistors in the

second part

dominate the overall conductance of the network. The critical conductance

is calculated as follows.

is calculated as follows.

The percolation subnetwork consists of conductances with

. Using

(1.6), this condition can be written as

. Using

(1.6), this condition can be written as

|

(1.9) |

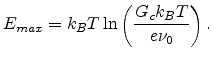

with

|

(1.10) |

|

(1.11) |

is the maximum distance between any two sites between which a

hop can occur, and

is the maximum distance between any two sites between which a

hop can occur, and  is the maximum energy that any initial or final

state can have. Thus the density of states that can be part of the percolating subnetwork is

given by

is the maximum energy that any initial or final

state can have. Thus the density of states that can be part of the percolating subnetwork is

given by

|

(1.12) |

Since the sites in the subnetwork are linked only to sites within a range

, this criterion has the form

, this criterion has the form

|

(1.13) |

with  being a dimensionless constant. A combination of (1.9) to (1.11) yields

Mott's law (1.8), with

being a dimensionless constant. A combination of (1.9) to (1.11) yields

Mott's law (1.8), with

.

According to the Miller Abraham equation (1.1) we can roughly calculate the

nearest-neighbor distance for an upward hop from an initial site with energy

.

According to the Miller Abraham equation (1.1) we can roughly calculate the

nearest-neighbor distance for an upward hop from an initial site with energy

to a finial site with energy

to a finial site with energy

from

the equations below [10]

from

the equations below [10]

|

(1.14) |

Here

is the DOS function. The hopping distance can be

calculated as

is the DOS function. The hopping distance can be

calculated as

![$\displaystyle R\left(E_f\right)=\left[\frac{4\pi}{3}\int_{-\infty}^{E_f}g\left(E\right)dE\right]^{-1/3}.$](img136.png) |

(1.15) |

So the corresponding hopping rate is

|

(1.16) |

Maximization of (1.16) over energy  gives the equation

gives the equation

![$\displaystyle g\left(E_f\right)\left[\int_{\infty}^{E_f}g\left(E\right)dE\right]^{-4/3}=\frac{1}{\gamma k_BT}\left(\frac{9\pi}{2}\right)^{1/3}.$](img139.png) |

(1.17) |

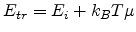

The finial energy  that maximizes the hopping probability does not depend

on the initial energy

that maximizes the hopping probability does not depend

on the initial energy  . This particular energy is called transport

energy

. This particular energy is called transport

energy  [10].

[10].

Arkhipov extended this theory to the effective transport energy

[18]. In this theory, the Miller Abrahams equation is rewritten as

![$\displaystyle \nu=\nu_0\exp\left(-\mu\left(R_{ij}, E_i, E_j\right)\right)=\nu_0\exp\left[-2\alpha R_{ij}-\frac{\theta\left(E_j-E_i\right)}{k_BT}\right],$](img140.png) |

(1.18) |

with the hopping parameter  and the unity step function

and the unity step function  . The average number

. The average number

of target sites for a

starting site with energy

of target sites for a

starting site with energy  , whose hopping parameters are not larger than

, whose hopping parameters are not larger than

can be calculated as

can be calculated as

|

(1.19) |

Neglecting the downward jumps and defining

|

(1.20) |

transform (1.19) into

|

(1.21) |

According to variable range hopping theory [19], a hop is possible if

there is at least one such hopping neighbor, i.e.  . This leads to

the following equation

. This leads to

the following equation

|

(1.22) |

If the DOS distribution decreases with energy faster than  then the integral on the left-hand side of (1.22) depends weakly upon the

lower bound of integration for sufficiently deep starting sites, and

(1.22) is reduced to

then the integral on the left-hand side of (1.22) depends weakly upon the

lower bound of integration for sufficiently deep starting sites, and

(1.22) is reduced to

|

(1.23) |

where  is the effective transport energy.

To investigate charge transport and charge

buildup in

is the effective transport energy.

To investigate charge transport and charge

buildup in  films, an analysis of hole transport has been presented which

is predicated on a model involving stochastic hopping transport. This

description, based on the work of Scher and Montroll [20], accounts for many

of the features of hole conduction in

films, an analysis of hole transport has been presented which

is predicated on a model involving stochastic hopping transport. This

description, based on the work of Scher and Montroll [20], accounts for many

of the features of hole conduction in  and has been termed the

continuous-time random walk (CTRW) model. A wide range of experimental

observation can be understood on this basis [20,21,22]. However, there has been some reticence to accept the CTRW

model completely because of observations that the apparent activation energy

for the charge collection process depends on the fraction of charge collected

[23]. This observation is at odds with the CTRW model as it has been

presented, since that model predicts universality, i.e., charge transport

curves obtained at different temperature should superimpose with a simple shift

in the time axis [24]. Although charge collection curves curves obtained at

different temperature do superimpose approximately, there is some deviation,

and this deviation is in the direction predicted by the multiple-trapping

model.

and has been termed the

continuous-time random walk (CTRW) model. A wide range of experimental

observation can be understood on this basis [20,21,22]. However, there has been some reticence to accept the CTRW

model completely because of observations that the apparent activation energy

for the charge collection process depends on the fraction of charge collected

[23]. This observation is at odds with the CTRW model as it has been

presented, since that model predicts universality, i.e., charge transport

curves obtained at different temperature should superimpose with a simple shift

in the time axis [24]. Although charge collection curves curves obtained at

different temperature do superimpose approximately, there is some deviation,

and this deviation is in the direction predicted by the multiple-trapping

model.

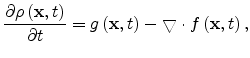

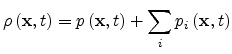

The multiple-trapping model for unipolar conduction is defined by the

following equations [12]

|

(1.24) |

where

|

(1.25) |

and

|

(1.26) |

Here

is the local photogeneration rate,

is the local photogeneration rate,  is the flux of mobile charge carriers,

the total carrier concentration is

is the flux of mobile charge carriers,

the total carrier concentration is

,

,

is concentration of mobile carriers,

is concentration of mobile carriers,

is the carrier concentration temporarily

immobilized in the

is the carrier concentration temporarily

immobilized in the  th trap,

th trap,  is the capture rate by the

is the capture rate by the  th trap and

th trap and

is the release rate.

is the release rate.

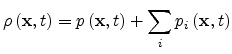

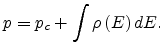

Later multiple trapping theory was extended for

disordered organic semiconductors as:

|

(1.27) |

Here  is the total hole concentration,

is the total hole concentration,  is the hole concentration in

extended states and

is the hole concentration in

extended states and

is the

energy distribution of localized (immobile) holes. Since carrier trapping

does not change the total carrier concentration

is the

energy distribution of localized (immobile) holes. Since carrier trapping

does not change the total carrier concentration  , the continuity equation

can be written as

, the continuity equation

can be written as

|

(1.28) |

with the mobility  and the diffusion coefficient

and the diffusion coefficient  . This equation assumes

two simplifications: no carrier recombination and constant electric field (no

space charge). Substituting the trapping rate

. This equation assumes

two simplifications: no carrier recombination and constant electric field (no

space charge). Substituting the trapping rate

|

(1.29) |

and release rate

|

(1.30) |

gives the following equation

|

(1.31) |

In equilibrium the energy distribution of localized carriers is

established, and the function

does not depend upon time

does not depend upon time

|

(1.32) |

Next: 1.4 Organic Light-Emitting Diodes

Up: 1. Introduction

Previous: 1.2 Organic Semiconductor Physics

Ling Li: Charge Transport in Organic Semiconductor Materials and Devices

![$\displaystyle I_{ij}=\frac{q\nu_0\exp\left(-2\alpha R_{ij}-\frac{\mid E_i-E_j\m...

...\left[\frac{E_i-\mu_i}{2k_BT}\right]\cosh\left[\frac{E_j-\mu_j}{2k_BT}\right]}.$](img105.png)

![]() of

semiconductors using reduced networks. They assumed that the statistical

distribution of the resistances depends only on

of

semiconductors using reduced networks. They assumed that the statistical

distribution of the resistances depends only on ![]() and not on the site

energies. This was justified because the experimental data for some

semiconductors indicated that the impurity conduction exhibits a well-defined

activation energy. But Mott [16] pointed out that the exponential dependence of the

resistances on the site energies can not be ignored in most cases. When a carrier

close to the Fermi energy hops away over a distance

and not on the site

energies. This was justified because the experimental data for some

semiconductors indicated that the impurity conduction exhibits a well-defined

activation energy. But Mott [16] pointed out that the exponential dependence of the

resistances on the site energies can not be ignored in most cases. When a carrier

close to the Fermi energy hops away over a distance ![]() with an energy

with an energy ![]() , it has

, it has

![]() sites to choose from, where

sites to choose from, where ![]() is the site density function. In general,

the carrier will jump to a site for which

is the site density function. In general,

the carrier will jump to a site for which ![]() is as small as

possible. The constraint to find a site within a range

is as small as

possible. The constraint to find a site within a range

![]() is given by

is given by

![]() . Substituting

this relation into (1.6) yields

. Substituting

this relation into (1.6) yields

![$\displaystyle G\propto \exp\left[-2\alpha R-\frac{1}{k_BT\left(4/3\right)\pi R^3\rho}\right].$](img114.png)

![$\displaystyle G\propto\exp\left[-\left(\frac{T_1}{T}\right)^{1/4}\right],$](img115.png)

![]() . Using

(1.6), this condition can be written as

. Using

(1.6), this condition can be written as

![$\displaystyle R\left(E_f\right)=\left[\frac{4\pi}{3}\int_{-\infty}^{E_f}g\left(E\right)dE\right]^{-1/3}.$](img136.png)

![$\displaystyle g\left(E_f\right)\left[\int_{\infty}^{E_f}g\left(E\right)dE\right]^{-4/3}=\frac{1}{\gamma k_BT}\left(\frac{9\pi}{2}\right)^{1/3}.$](img139.png)

![$\displaystyle \nu=\nu_0\exp\left(-\mu\left(R_{ij}, E_i, E_j\right)\right)=\nu_0\exp\left[-2\alpha R_{ij}-\frac{\theta\left(E_j-E_i\right)}{k_BT}\right],$](img140.png)